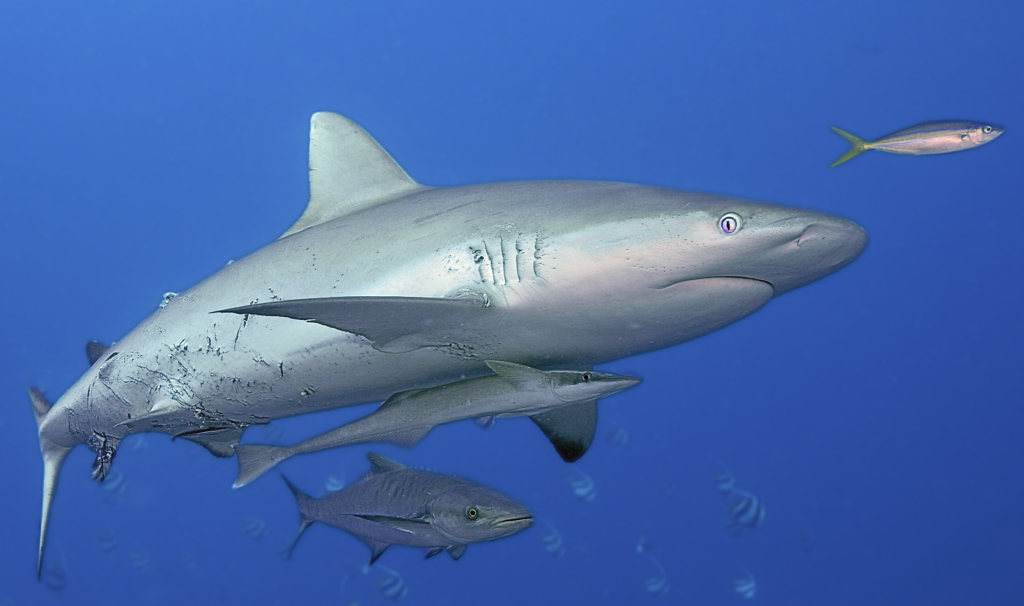

Every couple of months, during the last five years at least, Maldives’ social media sphere has churned out quite the shark-induced frenzy, with heated discussions surfacing over whether the archipelago’s famous turquoise blues have indeed become what some are calling “infested waters”.

For the local scuba-diving community, and environmentalists everywhere, an incline in shark numbers is heralded as the best of news. Since implementing a complete ban on shark fishing in 2010, Maldives has received worldwide applause for securing Indian Ocean’s own haven for these apex predators, particularly during a time when global fish populations are plummeting.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)’s 2020 report estimates that over a million species are currently faced with extinction. By 2015, 33 percent of global marine fish stocks were being harvested at unsustainable levels; 60 percent maximally sustainably fished and 7 percent were harvested at levels lower than what can be sustainably fished.

This year, however, the so-called debate to legalize shark fishing gained new traction following prickly comments made by the country’s Minister of Fisheries and Agriculture, Zaha Waheed, during a summons on March 23 by the Parliamentary Committee on Economic Affairs.

Speaking about the newly formed Fisheries Act (14/2019) which follows the previous (1987, Law No. 5/87), Minister Zaha revealed “This [shark fisheries] is also a [economic] resource, and there is no reason we should not benefit from it. Therefore, discussions regarding fishing for sharks in the open seas, and how we can open this up, are now in motion”.

On multiple occasions, this newspaper reached out directly to Zaha Waheed to elaborate on her comments but was turned down. It should be noted that these queries come at a time when the opposition has moved for a no-confidence vote on the Minister. Her cabinet position comes from a slot given to the Maldives Reform Movement, which is part of the incumbent ruling coalition.

At the committee meeting, North Thinadhoo MP Abdul Mughnee welcomed the news, responding that “The reality is that sharks are causing a lot of trouble, and I’m glad that the Minister has spoken of a solution. This is happy news, especially for fishermen”.

As one would expect from a heavily tourism reliant economy, powered by the draw of a pristine natural environment – once these recordings hit the Majlis’ (Parliament’s) Channel on Youtube, it was followed by widespread public outrage, fueled further by the recently reported cases of illegal shark fishing and trade in the Maldives.

Bigger Fish To Fry

In pursuit of logical arguments that may be presented for the legalization of killing sharks, whether managed or otherwise, we look at the law and regulations in place.

While Maldives’ fishing industry is centuries old, and deepwater shark fishery is known to have begun as early as the 1960s, the platform for international exports took off in a big way during the late 1970s alongside tourism. Nevertheless, 50 years later, fishing remains one of the country’s least regulated sectors. Certainly, there is need for more data to be made available, especially with regards to the country’s residential tuna stock, shark populations, and migratory patterns.

Yet, the island nation has successfully touted its industry as one of the most “sustainable” fisheries in the world, an argument that hinges on the use of the pole and line fishing method. Nevertheless, industrial sustainability must also be measured against its supply source; in this case, the number of tuna that can be reasonably caught without harming reproductive cycles and the ecosystem at large.

While tuna fisheries are well regulated in comparison to reef fisheries, according to the Fisheries Ministry, the Maldives is yet to calculate a “maximum sustainable yield” for tuna fishing. This is indicative of lacking concern, especially as the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) places the global stock status from 2019 to 2023 of yellowfin tuna at 90 percent. In general terms, yellowfin tuna has been overfished in the Indian Ocean since 2015.

In fact, in relation to sharks, there is not enough information collected to indicate that shark populations have recovered or that sharks are responsible for the “shortage in tuna” that is being reported by fishermen. Some statistics are available as to specific locations, but factor in the migratory nature of sharks, the vastness of the archipelago, and the data falls short of the requirement for viable, actionable projections.

So what does this all mean for the “discussions” that are “underway”?

Certain legal maritime experts recommend that the Fisheries Act remain as the legislative framework it was intended and that the ministry instead develop further, thorough regulations to ensure that tuna fisheries are well sustained, the livelihoods of fishermen are considered, coral reef ecosystems stay protected, that any introduction of foreign vessels and fishing methods would be controlled, so on and so forth.

They also maintain that, in order to do so, the ministry must first initiate comprehensive research, in addition to IOTC’s recommendations, and determine a solid baseline for theorizing recommendations and assessing regulatory amendments.

“Impossible to not harm them”

Given the lack of scientific surveys, it is reasonable to assume that much of the discourse that has recently taken place, be it for or against shark fisheries, amounts to little more than hearsay between fishing and tourism communities.

Speaking with several local fishermen, based in major fishing zones such as Haa, Laamu, Gaafu and Dhaalu Atolls, opinions ranged from staunchly against the fishing or finning of sharks, to being wary of their predatory nature.

“In short; without sharks, our fishing industry will cease to exist”, asserted Hassan Sajin, widely known by his social media handle ‘Zuvaan Masveriyaa’ (translates to young fisherman). “The last time I went fishing, we were in the presence of five sharks and still managed to catch over 10-15 tons of skipjack tuna. A couple of fish may have been snatched by sharks, but that is hardly a loss”.

“Personally, I’ve been fishing and diving, side by side, for years, especially around Huvadhoo Atoll. I’m staunchly against the introduction of managed shark fisheries. I never thought that the ministry would broach such a foolish topic, let alone pursue it”.

Further investigation implored this reporter to turn towards the specific path of ‘sports fishing’, itself a relatively new branch intersecting with the tourism and fishing industry, that attracts big spenders from across the globe.

“All of a sudden, there are a lot of sports fishermen. They’re jigging as well, looking for fish from much deeper waters. Sometimes in the same areas as commercial fishermen and outside the atoll as well. As they jig, their catch is reeled in at a fast speed, the movement jumpy and awkward – this serves as a trigger for sharks, which are naturally attracted to fish that seem weak or unwell. So, obviously, sharks coming to grab one’s catch is a more common occurrence in sports fisheries”, explained Abdulla Hasrath (Hathu), Dive Instructor and owner of Dive Club Maldives.

Hathu adds, “But at the same time, that seems to be the sport element as well – grabbing the catch before a predator steps in.”

In conversation with Imad Mohamed, a sports fisherman with a large following on Instagram, he expressed his opinion that indeed, sharks posed a unique challenge to his industry.

“We do face issues due to the shark population. Sports fishing requires expensive equipment, and if one gets tangled up in the bycatch, there’s no way we can save our gear without interacting with the shark. Therefore, it is impossible not to harm them”, said Imad. “It is very, very difficult to draw in a catch whilst avoiding a shark from eating it – I definitely think something should be done on this subject, and managed fisheries seems like a viable option”.

He added, “Just the other day, we caught a thresher shark. It was a magnificent specimen, and we took some photographs. People do react to such incidents strongly, but I fail to see an issue since we did release it.”

Dive Instructor Shaziya (Saaxu) Saeed disagrees. “They use expensive colorful lures that understandably, they must remove from the bycatch. But it doesn’t end there. These sharks, which cannot survive long out of the water, are then brought on board for promotional photography, which adds to the harm. There is a need for regulation.”

The “too many sharks interfere with our game” reasoning to lift the shark fishing ban, offered by some sports fishermen, takes a confusing turn, one that certain divers compare to “flashing a red card to a goalkeeper for successfully catching the football”. But not all sports fishermen tout such beliefs, either.

Imad countered the argument stating that it was a misunderstanding of the sport. “I believe that the sport of fishing is defined by type, technique and equipment. In my opinion, the issue with sharks comes down to this, it is symptomatic of an ecological imbalance and therein lies an opportunity as well”.

On the other hand, it certainly presents a different route for tourism enterprises. “I’ve worked in the tourism industry for a long time”, declared Almas, professional angler. “Earlier, we welcomed three types of tourists; honeymooners, beach goers and underwater enthusiasts. Things have changed now though, and we’ve seen the rise of fishing tourism. In Maldives, sports fishing is akin to golf, a luxury endeavor .”

He elaborated, “Not only is what we do sustainable, we practice catch and release. We don’t use live bait and we don’t condone any activity that is against the law – our clients would not tolerate that either. So, in my opinion, the sport fishing community would not enter the conversation about legalizing shark fisheries, we are a separate venture altogether”.

“On the subject of sharks, well yes, we do experience sharks as bycatch occasionally, but it is hardly a difficulty. We call it ‘tax’. And sure, just as divers want to take pictures with the largest creature and surfers want shots of particular waves, we also do the same before releasing them – that’s just marketing”.

But the blame cannot be solely on any party, sport fishing or otherwise.

Dangerous habits such as dumping garbage into the ocean, chumming the water prior to submersion, feeding sharks during guest activities are similarly problematic practices that tamper with the delicate ecological balance, therefore need to be identified and halted accordingly.

Rot From The Head Downwards

On the international environment platforms, the island nation has always placed itself at the forefront.

In this vein, Maldives’ statement on the IOTC’s Special Session concludes on the note, “…Maldives is alarmed by the lack of urgency and understanding demonstrated by a number of member states of the IOTC, and the lack of political will to address the matter”.

“Sustainability of the tuna stocks of the Indian Ocean is vital for coastal states, in particular, Small Island Developing States”.

Although the protection of natural resources is stipulated in the Constitution of Maldives, and despite being elected on pledges towards a ‘blue economy’, the Solih Administration has on several occasions, issued powerful statements as above, and failed to deliver on home soil.

Case in point; the rampant black market for products derived from endangered wildlife.

On December 15, 2020 the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) forwarded reports of illegal shark fishing to the Fisheries Ministry, which was responsible to investigate the matter as the issue falls under their mandate under the Fisheries Regulations. In March, the ministry received two further reports involving a Dhoni (local vessel) alleged to hail from Dhangethi, Alifu Dhaalu Atoll. During the first incident, police intervened at the lagoon surrounding Maavaru, Kaafu Atoll where four fishermen were found in possession of approximately 10 sharks, along with cut fins and salted shark meat.

Two days later, the same boat (as per local news reports) was caught on video in Alifu Alifu Atoll, near the protected dive spot known as ‘Fish Head’.

Presently, the Fisheries Act allows for a maximum fine of MVR 5000 (approximately USD 300) for fishing without appropriate licenses. The penalty for a first offence is a cautionary notice.

According to sources in Dhangethi, as of April 4, the alleged Dhoni had not received any form of warning.

“That a protected dive site such as Fish Head, is allowed to be exploited in this way, is of utmost concern”, says Diver Hathu.

According to multiple sources, the fact that parties based in Alifu Dhaalu Atoll, especially the island of Dhangethi, are involved in shark fishing is a well known matter. The rumor mill also points to similar practices in the outer corners of Male’ Atoll, and a secret warehouse in Hulhumale. However, Times of Addu was unable to confirm these allegations.

“The question to ask is, why is it being allowed to continue? There is a demand for it, and there are people willing to look past the negative outcomes for our shared environment”, said Dive Veteran Hussein (Sendi) Rasheed, founder of Villa College’s Faculty of Marine Studies.

As the debate on expanding fisheries ensues, all conversations seem contingent on “managing” the industry in order to protect the environment and the industry’s use of the highly marketable “sustainable fishing”, “shark-friendly” labels.

At the same time, particularly with regards to environmental issues and eco crimes, the government is notorious for its inability to monitor illegal activity and implement regulations.

“A lot of people know about these ongoing [smuggling of illicit items]. We’ve heard about them too, but there is a lack of action already”, confirmed Mohamed (Sindhi) Seeneen, Director at diveOceanus.

This is evidenced by the amount of shark jaws, teeth, corals, shells, turtle products (all outlawed for fishing and export, Maldives has been a part of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora since 2012), that are still found in souvenir shops around the country, to this day.

“And whilst such issues pass by unaddressed, we are hearing talk about a possible reintroduction of managed shark fisheries . But that [protocol enforcement] may not be a matter that everyone finds believable”.

Unfortunately, the events of March 2021 too seem to offer the same conclusion.

All for a single pay day

With all these factions vying for possible revenue that could be generated from sharks, pitting the profit derived from observing the creatures in their natural habitat, versus gains from utilizing their meat for consumption, decoration and beauty products, one market breaks surface as the clear winner.

A 2011 report sent to IOTC by the Fisheries Ministry states that, in 1992, Maldives tourism industry generated an income of USD 2.3 million from tourists arriving for ‘diving holidays’, whereas during the same year, the revenue raked in by shark fisheries was USD 0.7 million. This was the largest revenue recorded per annum pertaining to the export of shark fins and related products.

The nominal GDP for Maldives in 2018, published by the National Bureau of Statistics, reveals that the tourism industry accounted for 20.2 percent, whereas fishing amounted to 4.5 percent.

According to a research conducted by James Cook University, Australia prior to the shark fishing ban (2010), it was presumed that in Maldives, the value of a live shark (USD 3,000 for every year of its life) is a whopping 100 times greater for the Maldivian economy, per annum, than a dead one (USD 32 for every shark that is caught and sold).

In 2015, a study about the ‘How shark conservation in the Maldives affects demand for dive tourism’ showed that, at the time, the local diving industry was generating an income of USD 43 million – USD 154 million, the latter increase attributed to additional expenses made by the same tourists. The survey concluded that shark conservation increased demand for diving by 15 percent, earning an additional revenue of USD 6 million. It also puts a price on illegal shark fishing being showcased to tourists, stating that it may cause a downfall of 56 percent in demand and an economic loss of USD 24 million.

But more relevant to the economic gain is the simple exhaustibility of supply.

Speaking with numerous divers from all over the archipelago, their voices blended unanimously in the belief that, should shark fishing be allowed, authorities would struggle to manage the industry and it would not take long for the seas to be emptied, resulting in little more than “a single payday”.

Adam Ashraf (Asarey) who owns and operates Dive Desk emphasized, “Economically, there might be a short-term benefit [reaped from shark fisheries] but the long term environmental damage far outweighs any possible profit”.

Calls to sustain the ban

In the wake of the media coverage following Minister Zaha’s comments, a number of environment advocates have stepped forward to voice their concerns.

Over 200 local and international organisations, alongside tourism and fisheries-related businesses, have banded with Maldives Resilient Reefs to release a joint-statement urging that the state not lift the shark fishing and trade bans that have been in place for over a decade.

It reads, “With Maldives having declared a climate emergency, it is inconsistent for the country to undermine its position as a safe haven and hope-spot for sharks which play a vital role in maintaining the health of the Maldives’ marine environment”.

This has led to the formation of the Maldives #SaveOurSharks Alliance where the participating organizations are now busy raising awareness about the importance of sharks for the Maldives through their social media channels.

Similarly, a petition urging President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih to uphold the Shark Fishing Ban, started by ocean advocate Zaya Hassan, founding member of Maldives Shark Movement has gained over 20,000 signatories as of April 3.

On March 31, during a panel hosted by Ocean Geographic composed of scientists, NGO’s, divers and parliamentary representatives, Dr Sylvia Earl advocated for Maldives to remain a “hope spot” for the world.

“I like to think of them [sharks] as the guardians of the reef. The guardians of the ocean, in a way. They are so critical to the health of the ocean” said Dr Sylvia, American marine scientist, published author, lecturer, founder of Mission Blue. “If the ocean is not healthy then we are in trouble and nobody appreciates that more perhaps, than people who live close to the ocean.”

“Myself, and the entire organisation see in the Maldives, reason for hope. You’ve already taken action in a positive way to protect sharks. It really doesn’t make sense to reverse a decision that was really aimed at protecting the assets that make the Maldives valuable to those who want to come, and in exchange for revenue, have the opportunity to dive or to just be in the presence of a healthy ocean.”

Her sentiments were echoed by Hassan (Beybe) Ahmed, founder of NGO Save The Beach Maldives, “It is known that Maldives’ contribution to the global climate crisis is negligible, therefore reducing our carbon impact makes a small impact also. However, it is through actions like protecting sharks and other endangered species, nurturing our coral reefs and mangroves, that Maldives truly helps shift the narrative”.

“Protecting sharks is a major part of what we can do to save our planet. Saving these oceans is the best way we can try to save our home and sustain our way of life”.

Stewing in political broth

From the late eighties, until the ban was imposed, shark populations were dwindling in the Maldives. Once shark fishing was outlawed, however, numbers rose slowly to that which is observed today. This would mean that an entire generation of fishermen have never fished alongside healthy shark populations.

If that is a possibility, then it is clear that the country has not stepped in to fill any gaps of knowledge. Fishermen are not empowered with environment-based education, offered training to fish responsibly, nor involved in research and survey projects.

“Should the government be so inclined, there are a lot of people willing to offer their technical expertise and contribute to this field, in the interest of improved decision making, especially in these areas”, said Marine Conservationist Shaha Hashim, chairperson of Maldives Resilient Reefs. “Much can be achieved by fostering a culture of collaboration”.

“Advocating for sharks is not us standing against the fishermen.We are voicing out for their livelihood’s security as well. There is a lot of miscommunication in this regard. As primary actors, I believe the government should facilitate productive conversations. Instead we see solutions lagging behind politics”.

And where is the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) in all this?

“We do not believe the government of Maldives is considering such a decision [to overturn the ban], said EPA’s Director-General Ibrahim Naeem, during a call placed on March 30.

“The Ministry and EPA have not received any word, nor have we been consulted on such a matter”.

When pushed for an answer on when he would deem intervention necessary, Naeem insisted, “If legalizing shark fisheries formally enters the conversation then the EPA would stand firmly against it. We believe that there is no scientific evidence to support a removal of the ban”.

Similarly, the Speaker of Parliament Mohamed Nasheed, known for his environmental advocacy, has remained largely silent on this debate, much of which takes place on his floor. Though onus does not fall to the legislative body at this stage, the former President of Maldives is not known to hold back on his opinions and his lack of comment on the matter, to the ears of certain environmentalists, has spoken volumes.

“ My five year goal is to snorkel with my grandchildren and for them to see thriving schools of sharks I saw forty years ago”, iterated Diver Sendi, in an interview to Times of Addu. “With that, my future vote is contingent on the government beginning the right conversation on conservation”.

…And Thanks For All The Fish!

During the interview process numerous individuals came up to this reporter, asking about what the purpose of investigating shark fisheries and fish populations were, when plastic pollution, reclamation and coral bleaching continued to pose such a problem.

“When you can’t even save these reefs”, they argued, “what is the point?”

The answer is simple. To quote Aisha Niyaz, Vice President of Maldivian Red Crescent and Sustainability Consultant:

“We are at a time of grappling with multiple crises; pandemic, economic crisis, governance crisis, to name but a few. The climate and ecological crises are threat multipliers.”

Aisha Niyaz, Vice President of Maldivian Red Crescent and Sustainability Consultant

Aisha, who is also a member of the advisory committee for the IFRC-ICRC joint initiative in developing a Climate and Environment Charter, adds, “Lifting the ban will most likely push the ecological tipping points we are at the brink of”.

Hence, there is little time to reverse the problem, let alone take a step backward.

In comparison, the problem of overfishing or even increasing shark populations, becomes microscopic, one might even call it trivial.

The IPCC states with high confidence that with a warming of 1.5 degree Celcius, a further 70-90 percent of coral reefs will deteriorate. Furthermore, the World Meteorological Organisation earlier this year released a statement detailing a worrisome possibility that global average temperature may temporarily reach 1.5 degree Celsius by 2024.

Once we reach this point of no return, there is no conversation to be had about conservation of sharks, coral reefs or any other species. After our oceans die, we lose carbon sinks, oxygen sources, and an entire supply of food.

And at that stage, the only existential problem that we will be left to debate is our very own.